Anatomy of the Larynx

The larynx, or voicebox, is an organ in the neck that plays a crucial role in speech and breathing. The larynx is the point at which the aerodigestive tract splits into two separate pathways: the inspired air travels through the trachea, or windpipe, into the lungs and swallowed food enters the esophagus and passes into the stomach.

Because of its location, the larynx has three important functions:

- Control of the airflow during breathing

- Protection of the airway

- Production of sound for speech

The larynx consists of a framework of cartilage with surrounding soft tissue. The most prominent piece of cartilage is a shield-shaped structure called the thyroid cartilage. The anterior portion of the thyroid cartilage can be easily felt in thin necks as the "Adam's apple."

The larynx consists of a framework of cartilage with surrounding soft tissue. The most prominent piece of cartilage is a shield-shaped structure called the thyroid cartilage. The anterior portion of the thyroid cartilage can be easily felt in thin necks as the "Adam's apple."

Superior to the larynx (sometimes considered part of the larynx itself) is a U-shaped bone called the hyoid. The hyoid bone supports the larynx from above and is itself attached to the mandible by muscles and tendons. These attachments are important in elevating the larynx during swallowing and speech.

The lower part of the larynx consists of a circular piece of cartilage called the cricoid cartilage. This cartilage is shaped like a signet ring with the larger portion of the ring in the back. Below the cricoid are the rings of the trachea.

In the center of the larynx lie the vocal folds (also known as the vocal cords). The vocal folds are one of the most important parts of the larynx, as they play a key role in all three functions mentioned above. The vocal folds are made of muscles covered by a thin layer called mucosa. There is a right and left fold, forming a "V" when viewed from above. At the rear portion of each vocal fold is a small structure made of cartilage called the arytenoid. Many small muscles, described below, are attached to the arytenoids. These muscles pull the arytenoids apart from each other during breathing, thereby opening the airway. During speech the arytenoids and therefore the vocal folds are brought close together. As the air passes by the vocal folds in this position, they open and close very quickly. The rapid pulsation of air passing through the vocal folds produces a sound that is then modified by the remainder of the vocal tract to produce speech.

The diagram above on the left shows the folds in the open position. The folds should open like this during breathing. On the right, the folds are shown in the closed position as during speech.

Muscles of the larynx

Movement of the larynx is controlled by two groups of muscles. The muscles that move the vocal folds and other muscles within the larynx are called the intrinsic muscles. The position of the larynx in the neck is controlled by a second set call the extrinsic muscles.

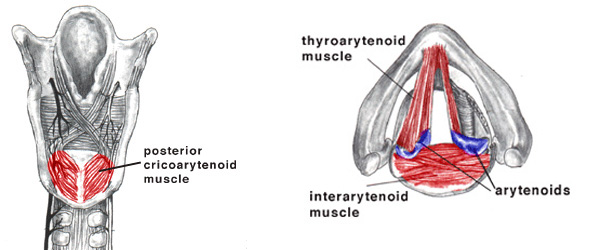

The intrinsic muscles are shown in the illustrations above. The vocal folds are opened primarily by a pair of muscles running from the back of the cricoid cartilage to the arytenoid cartilage. This muscle is called the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle (almost all the muscles in the neck are named by stating where the originate and where the end).

Several muscles help to close and tense the vocal folds. The body of the vocal folds itself is made up of a muscle called the thyroarytenoid muscle. A muscle called the interarytenoid runs from on arytenoid to the other and brings together these two pieces of cartilage. The lateral cricoarytenoid muscle, like the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle, also runs from the arytenoid to the cricoid cartilage. However, as its name implies it attaches to the lateral portion of the cricoid cartilage and is felt to primarily close the larynx.

The cricothyroid muscle runs from the cricoid cartilage to the thyroid cartilage. When it contracts, the thyroid cartilage tilts forward, putting tension on the vocal folds and thereby raising the pitch of the voice.

The extrinsic muscles are also called the strap muscles (since they look like straps). They do not affect the movement of the vocal folds, but they do raise and lower the entire larynx. This movement is especially important for swallowing. Trained singers also develop fine control of these muscles to help improve the quality of their voices.